No Recession

Real GDP is projected to grow by 1.8% in 2022, 0.5% in 2023 and by 1.0% in 2024.

USA Economic Snapshot, OECD October 2022

Recession

Two-thirds of those surveyed for the World Economic Forum’s Chief Economists Outlook expect a global recession in 2023

World Economic Forum 16th January 2023

No Recession

Real GDP Growth 2023 0.3%, 2024 1.8%

Congressional Budget Office Feb 2023 Baseline Forecast

Recession

Bloomberg survey of economists. February 2022/3

No Recession

“Is recession coming? Most corporate economists don’t see a slump happening within a year.”

USA Today, 24th April 2023

Introduction

The End of the Everything Bubble, the book I published in 2021, was a product of its time, a direct result of concerns over valuation levels and the apparently deeply rooted faith of market participants in the ability of governments and central banks to protect asset prices no matter the cost. The book sought to emphasize just how dangerous market valuations had become across all asset classes. These valuations seemed to be entirely contingent on an environment of perennially suppressed interest rates.

Arguing, implicitly or explicitly, that the cost of money would remain low indefinitely demands an underlying belief that the laws of economics had been abolished, or at least suspended. Most investors would not openly articulate such an argument.

Rather, the implicit view seemed to be that since it was impossible to predict when normality would return; it was too dangerous (to one’s career?) to diverge from the crowd’s thinking when the trend had been in place for such a long time.

The sanguine view of free money forever was rudely disturbed by the return of inflation. This forced the hand of central banks, which somewhat reluctantly have begun an inexorable journey back to some form of normalisation. Even now, although real (inflation-adjusted ) interest rates could not be described as particularly restrictive when compared to pre-global financial crisis norms, it has still been a shock to many investors who have grown accustomed to a cheap money environment.

As a consequence, there has been a small but meaningful reset on asset valuations, but the reset, in my view, is far from over. The complacent assumption that, if economic conditions deteriorate, there will still be a return to free money remains prevalent in many quarters. The return of inflation and rising interest rates, in other words, have not so far punctured the everything bubble completely.

The odds on a recession

As the prior quotes suggest, a casual observer could be forgiven for developing a degree of schizophrenia when following the changing prognostications of the economics profession regarding the likelihood of an economic downturn. The pendulum of sentiment swings from one side to the other on an almost monthly basis.

In reality the world has always had cycles of boom and bust. They are products of the human condition. That has rarely stopped policymakers from seeking to bend the cycle to their will, nor, on occasions, from proclaiming that the cycle has been abolished.

In 2006, for example, the UK’s Chancellor Gordon Brown repeatedly promised that there would be ‘no return to boom and bust’ in his budgetary statements to the House of Commons. The global financial crisis that erupted less than two years later exposed this claim for the foolishness it was. It forced Mr Brown, by then the Prime Minister, into a series of unprecedented economic measures to avoid a meltdown in the financial system.

The belief that the laws of economics can be bent or ignored without consequence has a long history in politics. It is a natural for governments to seek to prolong economic growth and defer economic downturns. This wish intensifies with the approach of elections. The normal measures adopted to achieve this goal typically involve an attempt is to bring forward future consumption and investment to boost economic activity.

Unfortunately, such measures invariably require the use of ever more debt to fund them. That in turn incurs a cost, which may not be apparent immediately if interest rates are suppressed, but will inevitably become so once the debt needs to be refinanced. Deferring the moment of truth encourages the naïve to believe there is no cost and the cynical to leave it for others to deal with at some later date.

It is not only policymakers who are susceptible to this form of myopia. Participants in asset markets are also only too willing to accept short-term distortions if one of the outcomes is higher asset prices today. When interest rates are being suppressed, the idea that the debt is effectively cost free can be – and often is – rationalised by “useful idiots”, as it was after the global financial crisis in so-called Modern Monetary Theory.

As an aside, this is not to suggest that macro-economic policy has no value, nor should it be confused with an argument about the appropriateness of Keynesian stimulus in certain conditions and stages of the economic cycle. It is simply an empirical observation that there will be a bill to pay for an extended period during which interest rates and other market signals are distorted.

What do we know?

Before turning to discuss whether we are heading into recession, it is worth reiterating some of what we do know about the current period.

- There has been a decade long period of interest rate suppression

- The build up in Government debt has only been exceeded during periods of war

- The ratio of total US debt to GDP has risen to levels that are unprecedented in peacetime

- Household debt as a percentage of GDP, although lower than in the run up to the GFC, remains very elevated by historical standards

- Corporate debt to equity ratios are approaching 100% for investment grade companies and much higher for weaker companies

- Credit spreads, while increasing, remain well below historic peaks

- Cyclically adjusted valuations of equity markets remain

Any one of these facts should be treated with alarm, but in combination they are both jaw dropping and unprecedented. In the modern world there has never been such an extended period of fiscal and monetary intervention, which is why it has spawned an ‘everything bubble’ of the kind that we now see. The recent surge in inflation has abruptly killed the idea of “lower for longer” interest rates and blown some of the froth off asset markets. But there is no reason to believe that this process has yet run its course.

While headline inflation, which includes energy and food price inflation, is falling and will continue to do so, so-called core inflation remains stubbornly above target in the US, Europe and the UK. The persistence of core inflation has already prompted sharp increases in interest rates to levels not seen since before the global financial crisis. In the process, while they still may have the desire, governments and central banks have lost the ability to manipulate the cost of money.

Where does this leave us?

What we do know should give more than pause for thought. In economic terms we have arrived at a crossroads, but one from which few easy paths follow. Much of the negative impact that an end to low rates will have on asset values may still be hidden from view in private markets, but these negative consequences cannot remain out of sight indefinitely.

Why would markets assume that distorting the cost of money for an extended period will not produce further undesirable outcomes? So far, we have only seen a relatively small number of examples come to the surface (as described in my earlier commentary ‘An Opera of Canaries’). There are many more precarious structures that made sense in a zero cost of money environment but not in a higher rate world. The chances are that they are endemic across the economy.

As the cost and availability of debt worsen, corporate failures will increase and investment decline. Households looking at their debts and a deteriorating labour market will pull back on their spending once the last of their Covid handouts work their way through. None of these developments are positive for economic growth.

The principal components of GDP are consumption, investment, government expenditure and net exports. If the forgoing is correct the first three are all set to decline. It is hard to tell the sequence, or indeed the catalyst for this happening, but it really does not matter. We begin from such a fragile position that it will take very little for sentiment to change and the economy to decline. It is a question of when, not if.

What would we need to believe for a soft landing/no recession?

Recessions can be seen as the natural consequence or corrective mechanism for prior excesses. On occasions they can result from some exogenous unforeseen event, such as Covid. The majority however are consequence of what has gone before. The technical definition of a recession is two successive quarters of negative real growth, but it is not unknown for technical recessions to be declared and then disappear with subsequent data revisions. For the general public recession tends to be perceived as a meaningful and prolonged economic downturn.

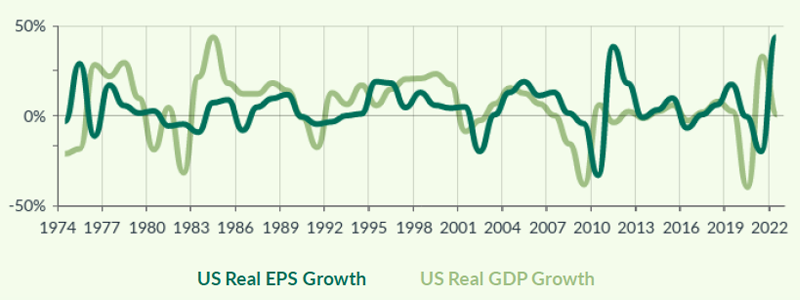

The relevant topic for asset markets is the potential for a substantive, prolonged recession, not one that might subsequently be revised away. Such recessions normally cause corporate aggregate profit declines of 20-30% or more. Not surprisingly, under these conditions asset prices are inevitably impacted, and markedly so if market levels were close to historic peaks before the downturn.

If we look at the components of GDP in turn, notwithstanding the lack of consensus in the economics fraternity, in my view it is hard to discern any credible routes to a soft landing, let alone to an outcome where recession is avoided. We can much more easily see scenarios where consumption stalls or declines. Investment is unlikely to accelerate now that interest rates are reacting to market forces and government expenditure is constrained by a backdrop of record deficits.

CONSUMPTION

Changes to private consumption are largely driven by changes in employment, household balance sheets and future expectations. Changes in total employment are particularly powerful factor. Currently what we can see are tight labour markets leading to rising earnings, increased total employment and falling unemployment. This would normally be a powerful combination for supporting growth.

However, we are in uncharted territory. We have not seen a pandemic-related shutdown before in which government intervention sustained both incomes and savings rates. Just how much current consumption derives from a post-Covid expenditure boom is not clear.

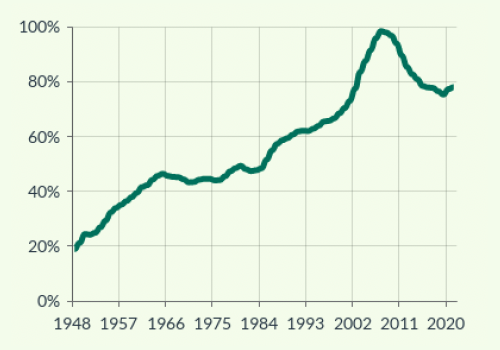

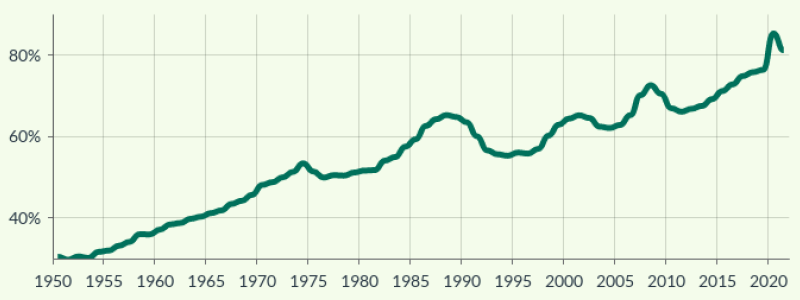

What we do know is that the current savings rate is at historic lows; household debt to GDP, whilst lower than the pre financial crisis peak, is elevated; household debt to disposable income remains above 100%; and equity withdrawal through mortgage refinancing has ground to a halt as interest rates have risen. On the other hand, reflecting the extended period of suppressed interest rates, many households have fixed debt repayments at historically low rates such that repayments, for the moment, are not an excessive proportion of income.

It is logical to assume that more stretched household balance sheets, the using up of ‘Covid savings’ and rising debt costs will eventually work their through to household spending, dampening consumption growth.

If this were to cause total employment to decline, a recession would be hard to avoid. In the postwar period a fall in total employment has always brought with it a recession.

Household Debt to GDP

Source: Bank of International Settlements. Total Credit to Households and Non-Profit Institutions Serving Households

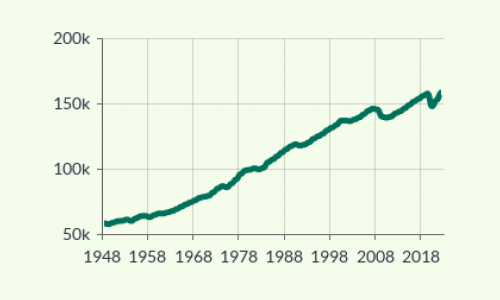

When one looks at the pattern of US employment the magnitude of the disruption from Covid is unmistakeable. Employment has grown at a reasonably consistent pace, more or less mirroring the growth in population. Population growth has been slowing however and the population is ageing, so we can expect employment growth to mirror this, whilst also bringing with it increased wage pressures.

So far as the short run is concerned, the post-Covid bounce appears to be fading and annual employment growth has recently dropped to 1.75%, having peaked at 10%. Total employment is approx. 158m which exceeds the pre Covid peak. Annual employment growth is now on a declining trend. In recessionary periods employment typically drops by around 1%, although it felt by almost 4% during the GFC and by a record 13% during the pandemic.

Consistent with the post-Covid bounce back, unemployment has fallen to 3.5%, below where it was before Covid.

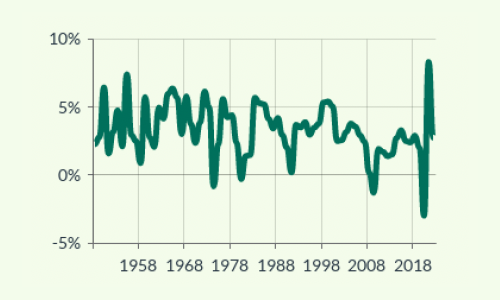

US Personal Savings Rate

Real Personal Consumption Growth

US Total Employment

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

INVESTMENT

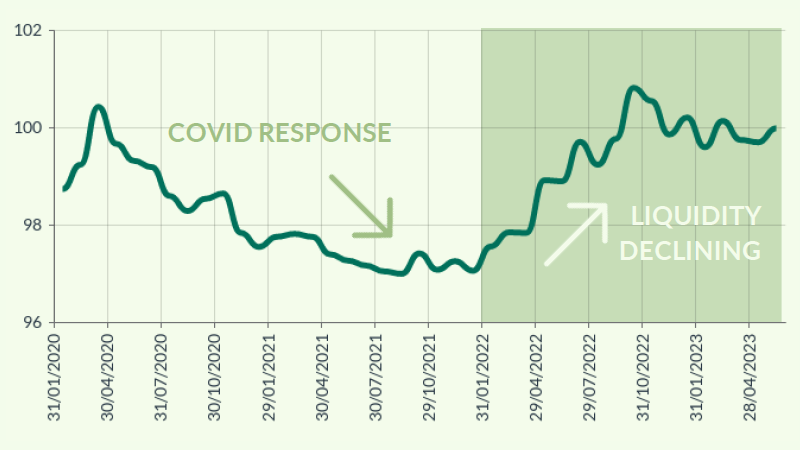

The rising cost of debt will impact household decision making and eventually flow through to the corporate sector in the form of lower demand. The increased cost of capital also raises the threshold for making investment decisions. From a period of abundant liquidity and low interest rates, we are now entering an environment where the ‘risk free’ rate is significantly higher and lenders will be more discerning about lending. There is early evidence of tightening lending standards, consistent with previous recessionary periods, although there is always the potential for Covid-related distortions.

Goldman Sachs US Financial Conditions

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

Meanwhile the corporate sector remains leveraged. Much is made of the cash balances residing on the balance sheets of the largest technology companies and it is true that in a number of cases the sums are breathtaking. However, this is not representative of the economy as whole. It should not be surprising that the reaction to suppressed interest rates has been to take advantage of the cheap debt on offer.

US Corporate Debt to GDP

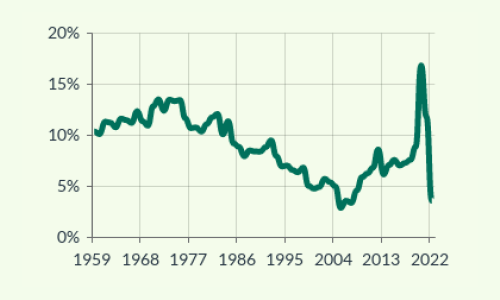

Real US Private Domestic Fixed Investment Growth

Source: IMF: Nonfinancial corporate debt, loans and debt securities (Percent of GDP)

The chart immediately above shows the path of private sector US investment. It underlines the magnitude of the investment downturn that followed the GFC. While interest rates have now risen in response to inflation, they remain negative in real terms. So, even if inflation turns down meaningfully it is hard to see nominal interest rates having much room to decline, unless we return to another period of deliberate suppression.

With companies facing a completely different funding environment than that of the past fifteen years, it is logical to expect an extended period of restricted credit availability, reducing investment further and acting as a drag on growth.

GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE

The United States has once again avoided an alarming breach of its mandated public debt ceiling following a last minute compromise between the Administration and Congress. As the pithy quote attributed to Winston Churchill says: “you can always count on the Americans to do the right thing, but only after they have tried everything else.” These days it makes more sense to substitute the word ‘politicians’ for ‘Americans’.

The point is that the entire developed world faces the same dilemma, namely how to deal with the debt that has been accumulated since the GFC. It involves hard political choices which will be unpopular with electorates. It is important to recognise that this time it is different. These are not deficits resulting from events, such as war or recession.

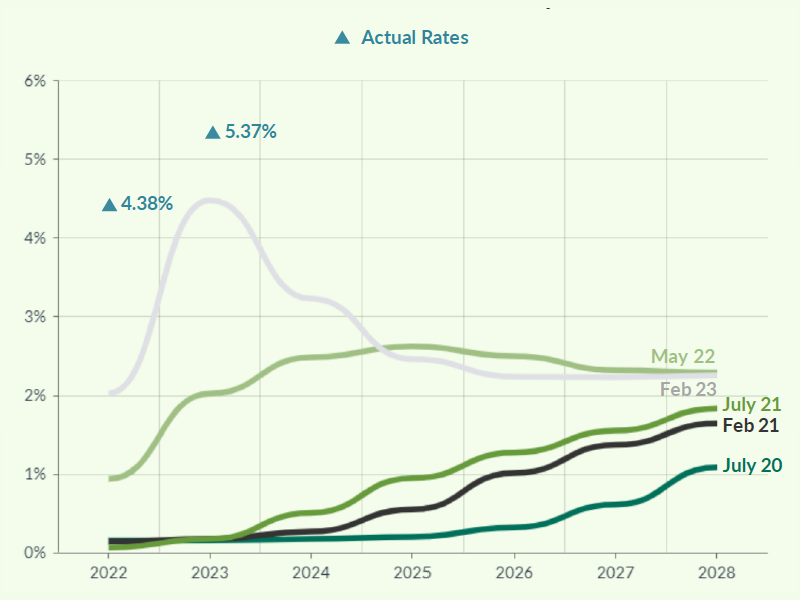

In the US for example, the deficit has been building since the millennium as parties of both hues have cut taxes and increased expenditure, whilst also having to deal with a financial crisis and a pandemic. The result can be seen in record debt to GDP numbers, while even on subdued interest rate forecasts the latest Congressional Budget Office assessments paint a scary picture. Current expenditure and tax patterns could continue, but at some point the pressure on bond yields will impose a binding constraint on what more governments can do. It is not simply the volume of issuance which could pressure yields. If core inflation persists, then investors will require ever higher compensation.

The current political debate around debt is mostly about attributing blame. What we do not see at the moment is any serious discussion about how debt reduction can be achieved, nor any attempt to explain to the voting public what is going to be necessary to achieve it.

Just to give a flavour of the magnitude of the issues, the most recent CBO report suggests the US fiscal deficit will remain around 6% of GDP for the next ten years. This based on the implausible assumptions that there will be no recession for the next ten years; that inflation falls back in 2024 and then remains well behaved; and that debt financing costs remain low. This is a singularly rosy scenario on all three counts.

Even then, the fiscal deficit is projected to remain at levels which ensure that total debt to GDP continues to expand to a point where it exceeds the World War II peak. The one thing we know is that this scenario will not happen. Reality will force current policies to be changed.

CBO 3 T Bill Forecasts Since July 2020

Source: Bank of International Settlements. Total Credit to Households and Non-Profit Institutions Serving Households

The main relevant conclusion here is that unless fiscal and monetary responsibility is abandoned altogether, then the net contribution to GDP from Government spending has to be, at the very least, less expansionary than for the past fifteen years and potentially meaningfully restrictive.

Putting it all together

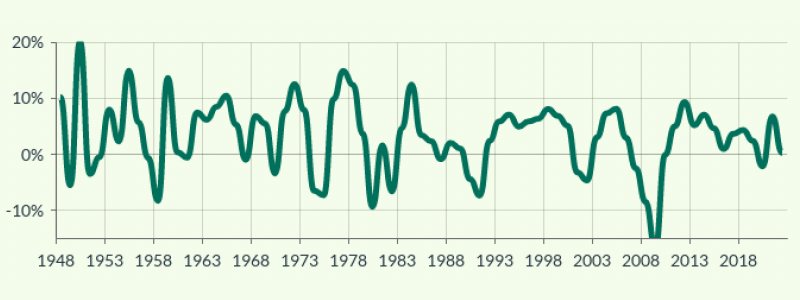

Analysed in this way, it is hard to see how this can lead to anything but a meaningful global recession in due course. On even conservative assumptions, the economy will shrink somewhere between two and four per cent if that turns out to be the case.

It is more difficult to be precise about exactly when the recession may begin. In this scenario fiscal deficits balloon as revenues shrink. Debates over choices will no longer be hypothetical. Revenue raising and expenditure cuts will become pressing issues.

Electorates will take notice of the outcomes and politicians will naturally seek both to assign blame and to find ways of avoiding making tough decisions. As fractured as the political system seems at the moment, one has to assume that current fault lines will only be accentuated under these conditions.

So far as equities are concerned, history suggests that, to use the US as an example, a ‘normal’ 2%+ recession is associated with earnings declines in the 20%+ range. One might surmise that a bear market of this nature is not one where a short sharp fall is then followed by an immediate recovery. Rather, given the nature of the economic issues that need to be resolved, it could take some considerable time for asset prices to recover.

US Real GDP and EPS Growth

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

The sovereign bond market is more difficult to call since the future path on yields will depend on the policy response and the extent to which inflationary polices are pursued. Whilst the absolute level of yields will be policy dependent, on the credit side one would expect spreads to widen sharply.

Notwithstanding the damage that tough economic conditions could do to credit spreads, perhaps the most exposed asset class is private equity. An era of low-cost money has inevitably contributed to both a higher volume of transactions and a lower perception of risk. Already we see pressure on valuation for cash hungry businesses as down rounds become increasingly common. This will increasingly be accompanied by failures at a range of marginal enterprises as liquidity drains and risk tolerances drop.

We have not yet reached the stage where confidence has evaporated. The display of animal spirits and exuberance associated with anything to do with Artificial Intelligence clearly demonstrates significant pockets of free capital still remain. It is understandable that AI is a focus for investors, given its undoubted potential. What is striking is the lack of discernment being applied in the investment process.

So then what?

Let us assume that the forgoing is correct and that a nasty recession unfolds. In the initial stages asset markets may react positively on the assumption that inflation will remain on a declining path and that the post GFC policy tools will be dusted down and re-employed. It is certainly possible that monetary policy could be loosened at this stage, but given the fiscal position, expansionary government policy would be much more difficult to pull off. In reality one would expect to see governments scrambling to find ways of raising revenues and reduce expenditures.

However, the political and policy background is a key determinant of how this may all unfold. As Keynes put it: “Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back”. The economic ‘orthodoxy’ prior to the GFC was fairly clear and largely consistent with the Volcker/Thatcher/Reagan policy initiatives of the 1980s. These were a direct reaction to the failure of a succession of interventionist initiatives during the 1970s. These measures both sought to ‘assist’ growth and counter the inflationary spiral which followed the 1973 oil crisis. The period was characterized by industrial strife, fiscal deficit issues and currency instability. The reasons why interventionism fell out of favour now seem to be a fast-fading institutional memory. We have seen the gradual encroachment of government in ever increasing attempts to seek to influence or control the economic cycle. The drift towards greater government intervention may have already been in evidence prior to the GFC but it has clearly accelerated since then, particularly in response to the economic crisis engendered by Covid. This is not intended to be a critique on the appropriateness or otherwise of any actions. It simply to note that governments are now much more prone to intervention and electorates are much more receptive, or even demanding of such actions.

It is hard therefore make any definitive, generalized statements on the potential initial policy response. What is likely is that the downturn will initially be met by lowering policy rates. How far this can go will depend very much upon the path of core inflation, but if one assumes a degree of stubbornness the scope of interest rate reductions will be limited by market reactions unless governments find a route to forcing compulsion on purchases.

Given the debt overhang this also applies on the fiscal side. There is certainly a much larger constituency in favour of government intervention than at any time since the 1970s. The degree of intervention favoured is not uniform and varies both within the Western world (e.g. US vs Germany vs France etc.) and between Asia and the West. Hence the only strong conclusion is that greater intervention is more likely than not. The exact form intervention might take will naturally be conditioned by the interaction of domestic politics and the degrees of freedom tolerated by global capital markets.

A fork in the road with two unattractive paths

An extended period of economic difficulty, which appears the most likely outcome, would certainly dampen inflationary pressures, but simultaneously witness a drying up in liquidity accompanied by significant declines in asset prices. As inflation declines in response to economic weakness, the attractiveness of fixed interest instruments will increase.

At some point the economic catharsis would wane and economic recovery will begin. The profit shock to equities from the economic downturn mean that valuations should have dropped sufficiently to create attractive opportunities for the investor brave enough to anticipate economic recovery. This is a well trodden path but extremely difficult to put into practice. ‘Buying at the point of maximum pessimism’ depends on being able to spot when sentiment is at its worst, which is only likely to be obvious ex post.

If on the other hand the recent policy trends were to continue, perhaps we could see a further drift toward to the interventionist approach of the 1970s. In that case the rules of the game would be significantly different. For example, if the result was a prolonged period of stagflation, fixed interest would be the last investment one would wish to own. The focus would instead be on trying to preserve purchasing power from the ravages of inflation against the backdrop of anemic growth.

These are only two potential outcomes and clearly there are a large number of potential gradations that could emerge. Looking at the different ends of the spectrum is helpful because it highlights the need to understand the possible policy responses and hence to consider the differential impact on individual asset classes.

In turn, understanding how policy will evolve has to take account the competing agendas in each case. These will vary both between continents but also within regions. For example, it is not hard to imagine that the French electorate, and hence policy makers, will behave very differently to the Germans in response to economic turmoil. The US environment is clearly highly polarised and facing a Presidential election whose outcome is far from clear. When economic troubles appear, a blame game inevitably kicks into action. One only needs to see the tinderbox that exists in France to realise that we are in for turbulent times.

If these tensions were not enough we also have inter-regional fractures appearing between the superpowers, as evidenced by both the Ukraine war and the mainland China threat hanging over Taiwan. None of these political and diplomatic issues are likely to lose their force against a backdrop of economic stress.

Patience is more than a virtue, it is a necessity

It would be easy to become irredeemably gloomy given the backdrop described above. However, it is important to remember that these are the very circumstances which give rise to the greatest investment opportunities. If one wishes to be ready to take advantage of them when they appear, the first order of the day is to make sure that capital has been preserved to make this possible.

The second order is to try and ensure that there is a degree of understanding of the various scenarios that might unfold which then allows an investing framework within which one is able to properly evaluate value as a precondition to allocating capital to the most profitable areas.

To my mind therefore this is an exciting time to be an investor. Analysis, as always will be important and as this note suggests, a great deal of effort is being

devoted to understanding how the global economy will evolve and what this may engender as a result. This does not mean that bottom up analysis no longer carries value. It simply acknowledges that we are in unprecedented economic times which demands that the ramifications are understood and factored into asset prices.

The partner of analysis is patience. Asset markets have short cycles within the longer- term trends where exuberance waxes and wanes. It is very easy to be sucked into these cycles and hence it is critical that one is possessed of patience and not to become overly concerned with shorter-term asset price movements.

This information is intended to be of general interest only and should not be considered as an offer, investment recommendation or solicitation, to deal in the shares of any securities or financial instruments.

Investment involves risk. The value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up and an investor may get back less than the amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future results.