John Scott Haldane was a physician and physiologist on the academic staff at Glasgow University. Known as the ‘father of oxygen therapy’ he was famous for his research in respiration and anaesthesia. His pioneering work gave rise to life-saving inventions ranging from respirators, gas masks, oxygen tents to decompression chambers and tablets. The research was conducted at no small risk to his own health, since part of the investigative process frequently involved self-experimentation (no volunteers being available!). In effect he was measuring and calibrating the effects of poison on himself.

One area of study was concerned with the high number deaths occurring in coal mines as a result of various forms of accidents. Haldane’s investigation determined that toxic gases were responsible for a large proportion of mining deaths. The identification of carbon monoxide as the lethal constituent led Haldane to focus on potential early warning systems and ultimately the introduction of canaries in mines as early detectors.

Canaries were selected for this task, because flight and altitude required a rapid metabolism and with it very high oxygen requirements. This made canaries highly susceptible to oxygen deficiencies and therefore ideal for indicating a drop in oxygen levels and hence the presence of deadly carbon monoxide. Their use in coal mines was widespread and they performed this task for almost a century, only being replaced in the mid 1980s by electronic gas detectors.

Over the period it would be hard to over-estimate the number of lives saved by this early warning system. On a humanitarian note, perhaps unsurprisingly, the miners became deeply attached to the canaries and the canary cages typically incorporated mini-respirators to ensure that the birds survived.

Is there such a thing as a canary in the mine for financial markets? Haldane’s research methods may provide some clues. His investigation began with studying the characteristics of the victims of mine disasters, which then led to the identification of carbon monoxide poisoning as the root cause. The relevant comparison here is that we know that since the global financial crisis (GFC) the cost of money has been deliberately suppressed for an unprecedented period.

We also know that when market signals are distorted, it typically leads to outcomes which only make sense in this distorted world. When these distortions are removed, the new calculus can lead to very different outcomes. So, the question for markets is whether the series of financial dramas we have seen unfold in the last few months – the gilts fiasco in the UK, the collapse of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and the demise of Credit Suisse – should be seen as isolated incidents or rather as warnings of profound underlying systemic problems.

My answer is not only that these separate incidents should be seen as warnings about further troubles to come – the collective noun for a host of singing canaries is an “opera”, incidentally – but that they are all clearly linked. They all stem ultimately from the same underlying cause, which is the extended period of zero cost money that was introduced in response to the global financial crisis of 2008.

The fiscal and monetary response to the global financial crisis created a new set of incentives which it soon became clear would in due course lead to misallocation of resources and dangerous amounts of leverage and risk-taking. It was always going to end badly, although we did not know precisely when or how.

A day of reckoning

We know now that the day of reckoning is upon us. Although they have been treated by many participants as shocks, the FTX, SVB and the autumn UK pension fund crisis should more realistically be seen as accidents waiting to happen and harbingers of more disruption to come. The financial world’s canaries, in other words, are progressively falling off their perches.

Cryptocurrencies

The collapse of FTX and the arrest of its founder Sam Bankman-Fried is not an isolated example of trouble in the crypto world. To see why you simply need to list some key characteristics of cryptocurrencies:

- Largely unregulated

- Largely unsupervised

- Almost zero transparency

- No audit trail

- No asset backing

Leaving aside the superficial mystique of mining, distributed ledgers, blockchain and the association with ‘tech’; the popularity of cryptocurrencies has largely stemmed from their rising prices and the stories of freshly minted millionaires who put their money into either the currencies or their ancillary operations, such as the provision of digital wallets and exchanges.

Traditional investment normally begins with a requirement that there should be no ambiguity about the application of the law of property rights. Due diligence is then conducted to ensure that those rights exist and can enforced. At this early stage it should not be relevant whether the asset happens to be rising in price or not.

Unfortunately, human nature makes many people truncate this part of the process for fear of missing out on the opportunity that rising prices appear to be offering. Consider for example the disastrous ‘due diligence light’ acquisition of ABN AMRO by RBS. Instead of due diligence we see confirmation bias; the sight of others rushing to participate endows the potential investor with a false sense of security.

Those who warn about the risks are typically given short shrift and accused of ignorance. At first sight, you would certainly think that cryptocurrencies, being as risky and opaque as they are, would inspire caution rather than wild enthusiasm. Yet, as in so many other cases, the liquidity injections from Quantitative Easing (QE), although initially successful in stabilising the financial system and encouraging lending, later generated very different outcomes as markets came to the view that the policy was in place for the foreseeable future.

As the policy mutated into what came to be perceived as an asset price support mechanism, in practice it had exactly the opposite effect as investor perceptions of liquidity and risk were distorted by the seemingly everlasting supply of free money. Now that all this liquidity is being withdrawn, many of the rags to riches stories have turned out to be an illusion and, in some cases, examples of downright fraud.

LDI Investing

In the autumn of last year, the attention of the world’s financial markets turned abruptly to the UK. Caught in the headlights were Prime Minister Liz Truss and Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwarteng and their radical tax cutting budget. It prompted a dramatic market reaction. As gilt prices tumbled the Bank of England had to step in to prevent numerous pension funds from imploding as the value of their leveraged holdings of gilts went into freefall.

Perhaps understandably, the focus of the watching world has been on the political ineptitude of the short-lived Truss/Kwarteng administration and its likely political consequences. The severity of the market reaction led to the exit of the PM and Chancellor and their replacement by others. There have been three Prime Ministers in twelve months and four Chancellors in four months.

The crisis in the gilt market and pensions system is still however seen by many as a temporary discontinuity which was successfully addressed by the prompt action of the Bank of England. Yet it is the implications of the problems on which the gilts fiasco shed a light, including the hidden risks that pension funds were accumulating on their balance sheets, that should be of most importance for investors.

When you have an extended period in which interest rates are suppressed below their natural market level, financial mishaps are bound to happen. Decisions which would in different times have been viewed as unthinkable instead become the norm. Risks are no longer seen for what they are. The longer the cost of money is maintained at artificially low levels, the more complacent markets become and the greater the risk of unintended consequences.

The tools employed to save the economy after the global financial crisis were inevitably taken in haste, as speed was of the essence to avoid the very real risk of implosion of financial system and the descent into a replay of the 1930s. Yet, although successful in the short term, the policy measures were kept in place for far too long. Ultra-low interest rates subsequently prompted a global search for new sources of investment income, or yield well beyond the time when it needed to be prompted by monetary measures.

In the case of UK pension funds, the search for yield led them to turn to so called liability-driven investment. These structures used leverage to juice the returns from the apparently low risk gilts and bond and free up funds to invest in higher risk/return assets to help cover their pension funding gap. When gilt yields soared in response to the disastrous Truss/Kwarteng Budget, the funds suddenly faced being forced to liquidate the very assets whose falling price was creating the increased collateral requirements.

But for the Bank of England’s intervention, the resulting downward price spiral could easily have ended up wreaking havoc on financial markets in the same way that portfolio insurance helped precipitate the famous stock market crash of 1987. This should have been – but wasn’t – a salutary experience which caused investors to worry where else the search for yield might be building up problems. It was a classic canary in the mine.

The liability driven investment episode is an illustration of what can happen when leverage and illiquidity collide. Whilst political ineptitude can be blamed for creating the rapid rise in bond yields, the fallout revealed how fragile the financial system was becoming. It is not as if we have not seen this movie before – just think back to the savings and loan crisis of the 1990s, the precipice bonds saga of the next decade and the complex derivatives that sunk the banking system in the run up to the global financial crisis.

In all these cases sophisticated financial models were presented to suggest that the probability of an ‘extreme’ event that could threaten solvency was low and hence taking on additional risk was not unreasonable. When tested in the real world, these models failed to live up to their billing.

Silicon Valley Bank

SVB was at the nexus of a number of revealed beliefs spawned by quantitative easing. The first was that liquidity would always be available when needed and that the cost of money would remain sustainably at or around zero. The second was that valuations of private equity investments represented a true and fair view of realisable value, rather than being based on the prevailing assessment of like-minded bullish investors.

These beliefs fly in the face of simple economic laws. Historically, the market has always required a positive real return from investing in bonds. To bet the bank on the assumption that bond investors will instead be happy to accept negative real returns indefinitely flies in the face of all experience. Even if the bonds are ‘risk free’ US government bonds, they are only risk-free in the sense that the US government will honour its liability to repay the principal if held to maturity. There is no guarantee that they will hold their value.

Some will blame the Federal Reserve for precipitating problems in the banking system by switching belatedly from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening, but that is to point the finger in the wrong direction. The finger has to point at those who were willing to assume that the laws of economics could be subverted indefinitely.

One by-product of the new QT regime is that investors can now obtain higher nominal returns on their cash through buying money market instruments and government guaranteed paper. They offer higher rates than the minimal rates of interest that banks offer their depositors. Eventually depositors start to take note and shift their money elsewhere to obtain higher returns.

For SVB, when cash started to go out of the door, a combination of private equity mark-downs, illiquidity in private equity assets, losses on their bond portfolio and an inability to raise new capital created the classic conditions for a run on deposits, leading to it having first to be rescued and then driven into bankruptcy by the authorities. The remnants have since been taken over by another bank.

The market has been panicking over potential insolvencies at other banks and more generally the lowering of expected profits on the realisation that banks will have to pay a competitive rate to hold depositors on the one hand and gradually diminishing economic expectations on the other.

The bigger spectre stalking the party is whether this all presages a repeat of the global financial crisis when it seemed at one point as if all the world’s biggest banks were about to become insolvent. There is good and bad news on this. A repeat of the systemic risk we saw in 2008 does not appear likely. Capital buffers are in much better shape and here has been no repeat of the pernicious off balance sheet structures that fuelled the collapse of Lehman Brothers and other banks.

What is more likely is simply that some banks, those which have got some big decisions wrong, and their shareholders will suffer the consequences and disappear, as Credit Suisse has just done. Clearly, fractional banking requires the ability of institutions to retain the confidence of its customers. A bank that fails, but where depositors rather than risk capital providers (i.e. bond and equity holders) are protected should certainly concentrate the minds of shareholders exposed to such institutions.

The market may shudder, but the threat of a systematic banking crisis will recede. However, there will undoubtedly be ripple effects which will serve to further drain liquidity and increase the cost of risk capital. A rising cost of capital can be a sign of systematic risk. Equally it can simply be a sign that conditions are normalising.

If we are heading to more difficult economic times then banks must incorporate this in their customer pricing. Similarly, providers of capital to banks must take into account the likelihood of greater bank loan defaults and hence higher loan loss provisions. Rising rates and widening spreads are a logical next step for a banking sector which has operated in a distorted framework for such an extended period. They do not necessarily point to systematic risk in the banking sector such as was in evidence during the GFC.

Where next?

The most dangerous element in the reaction of market participants to these successive events is a still pervasive narrative that the potential negative economic effects will stimulate a return to the days of zero cost of money, with central banks once again riding to the rescue with rate cuts and plentiful supplies of liquidity. This is absolutely the wrong inference to draw.

This is because these canaries in the mine all stem from the same root source. As mentioned previously, the background to the current situation lies in quantitative easing, introduced after the GFC as a response to the risk aversion induced in lenders by concerns over the robustness of the financial system. The central banks suppressed interest rates as part of a deliberate policy of forcing lenders to seek yield and move further out on the risk curve.

As a response to the conditions of the time it was a policy which seemed entirely appropriate. A decade and half later, it was no longer appropriate, nor sustainable. The absence of inflation, combined with fears of being seen to remove the support too soon, caused the QE regime to remain in place well beyond the point where it was required to secure the viability of the financial system.

It instead morphed into being a monetary policy that effectively existed to allow continued fiscal expansion by minimising the cost of government borrowing. There is little doubt that, if inflating asset prices and encouraging risk taking were the goals, then the policy has been an unalloyed success. But there are other factors which should have been taken into account and one of them – the sudden surge in inflation – now means that there can be no easy return to the easy money policy. The central banks are no longer in a position to make supporting asset prices and financing government debt their first priority.

Short interest rates have risen to combat inflation while the introduction of quantitative tightening seeks to reduce the debt held on central bank balance sheets. It is not unreasonable to suggest that, if followed through, this will have the effect of reducing risk appetite and lowering equity and bond prices – though by how much will depend on the pace at which it takes place.

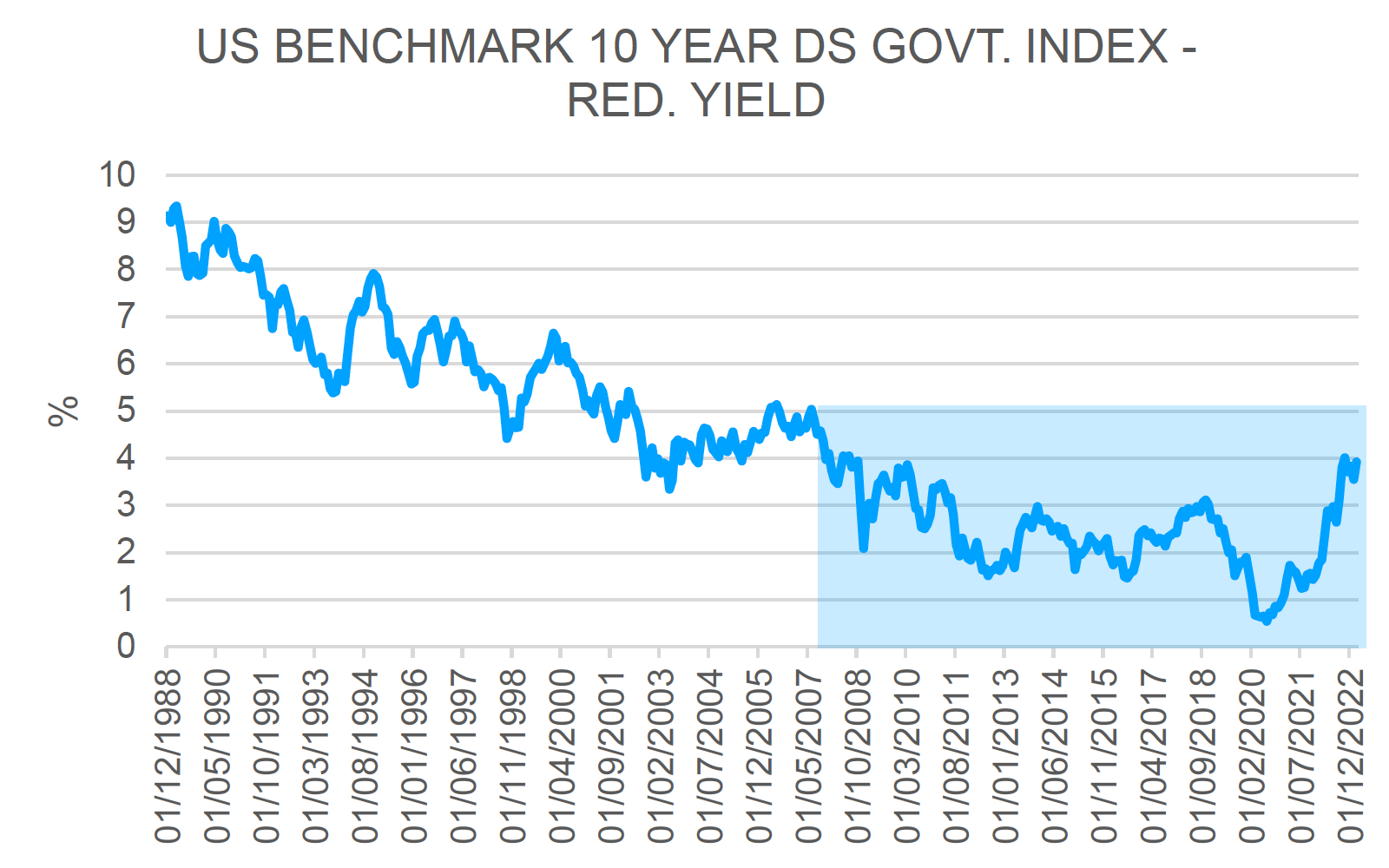

There is likely to be significant pressure to reverse course whenever negative economic news emerges, but the scope for reverting to the earlier policy is limited. If the central banks are no longer suppressing yields, then raising finance will need to take place on market clearing terms, something that has not been the case for more than a decade. As is obvious from Chart 1 the current US ten year yield, which is ranging between 3%-4%, is not anomalous by historical standards.

Nor can it be seen as restrictive in and of itself. That there is a significant body of opinion which views current monetary policy as ‘tight’ only serves to demonstrate how pervasive the impact of the post-GFC period has been in framing asset market expectations. At a technical level the supply of debt instruments is going to rise and demand decline. Governments’ undated appetite for debt will inevitably squeeze yields higher across the board.

The debt service cost for government is already significantly higher than the unrealistic forecasts of just 12-18 months ago. To finance existing US government plans, debt service costs will rise to exceed the cost of major entitlement programmes such as Medicare or Social Security, according to Congressional Budget Office projections. Even with what are arguably very rosy assumptions, these results are scary.

The worries to come

The logical conclusion is that markets will demand a fiscal retrenchment of meaningful proportions, with inevitable consequences for the rate of growth. What is not clear is how this will unfold. It could simply be slowly growing pressure on yields and a recognition that the fiscal deficit cannot be funded without spending reductions. Alternatively, there could be a blow-up in the financial system, akin to the LDI example in the UK.

Either way, while there may well be periods of instability, market pressures mean that the financial system is set to move away from the unconventional and damaging monetary policies that have characterised the past 15 years towards more conventional policy options. That means budget deficits will have to be financed and politically tough economic choices made against a recessionary backdrop. History is very clear that this does not happen in a smooth manner and social unrest is the very least that should be expected.

In this new environment of rising uncertainty and fiscal retrenchment, my expectation is that concerns over inflation will in due course be replaced by worries about growth. The investment pendulum will start to swing back from focus on returns to focusing on risk. The veil will be pulled back on the investment constructs and untested valuations which flourished during the QE period.

All sorts of leveraged structures, both inside the banking system and outside (the so-called shadow banking world), appeared to make sense before, but will be now revealed as simply products of a febrile and unsustainable environment that no longer stack up in a more normal world.

FTX, LDI and SVB are not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern and just like the canary in the mine give advance notice of the unseen dangers that lie in wait for those lulled into a false sense of security by the easy money era. This cycle will in due course create existing new investment opportunities, but what the canaries in the mine are telling us is that the process of readjustment has to run its full course first.